Left very early Saturday morning on work/semi-vacation trip to Florida, and probably won't be posting for a few days. Check back soon.

New York City, Ground Up: The built, the virtual, the bizarre, the wonderful.

I was also impressed with the simple quality of work. Any aspiring designer would be thrilled to produce the crocheted dresses and "personal panels" (below). It's amazing that the same person who welded together escape vehicles also made watercolors and knitted tops.

I was also impressed with the simple quality of work. Any aspiring designer would be thrilled to produce the crocheted dresses and "personal panels" (below). It's amazing that the same person who welded together escape vehicles also made watercolors and knitted tops.

The corporate "graffiti" thing has been cracking me up for awhile now ... you know the street advertisements for things like Hummers that are made to look like graffiti. Taking it to a whole new level is the new branch of North Fork Bank at the corner of 2nd Ave. and E. 10th Street. I noticed it a couple months ago when the branch was under construction: "graffiti" inside the bank, underneath the teller windows.

The corporate "graffiti" thing has been cracking me up for awhile now ... you know the street advertisements for things like Hummers that are made to look like graffiti. Taking it to a whole new level is the new branch of North Fork Bank at the corner of 2nd Ave. and E. 10th Street. I noticed it a couple months ago when the branch was under construction: "graffiti" inside the bank, underneath the teller windows. We think of the last five years as a unique time in the

We think of the last five years as a unique time in the The Story of New York House was first published in serial form in Scribner's magazine in 1887. It is a lovely bit of historical fiction (although that term wasn't yet coined), which begins in 1807 and takes place over several decades. The story, or allegory, is about the inexorable march of development followed by decline and finally transformation.

It was written by H.C. Bunner, a prolific urban journalist, fiction writer and editor who lived and worked in

Anyhoo, H.C. Bunner, in addition to being a great humor magazine editor and novelist, was also a serious urban journalist, chronicling life in

"The great city spreads itself day by day ... crawling ceaselessly northward, it divides and subdivides its habitations; gardens disappear and tenement-houses rise; every man’s allowance of space is cut down to its lowest possibility ... And there is still not room. One day, a full block of brown-stone houses, climbing up the rocks by Central Park, cuts right into a gypsy camp of superfluous poor, squatting outside the gates—a peaceable and well-organized colony that could not find room for itself in the regions of brick and mortar."

Bunner clearly spent a lot of time at the “gypsy camp” to write Shantytown, which might have been the first “experiential journalistic” piece to chronicle the life of the poor. It was published in 1880 and Jacob Riis’ How the Other Half Lives, which first appeared as an article for Scribner’s magazine, wasn’t published until 1890. (Interestingly, the Scribner's article was accompanied by illustrations that were drawn from Riis’ photos, even though it would later be his photojournalism of the poor that he became famous for.) What’s more, Bunner’s style in Shantytown and all his other urban chronicles was neither paternalistic nor moralistic, and brings a recognizably modern sensibility to subjects that were either ignored, pathologized or romanticized.

I keep thinking I'm going to undertake a long-term project to resurrect H.C. Bunner as a very talented urban journalist. But until I get to it, for more info on H.C. Bunner, click here. For the entire series of The Story of a New York House, links are below.

The Story of a New York House, Jan. 1887.

The Story of a New York House, Feb. 1887.

The Story of a New York House, Mar. 1887.

The Story of a New York House, Apr. 1887.

The Story of a New York House, May 1887.

Since I'm on a transportation kick, I thought I'd do a little round-up of transportation alternatives that probably won't ever happen, despite people's best efforts.

Since I'm on a transportation kick, I thought I'd do a little round-up of transportation alternatives that probably won't ever happen, despite people's best efforts.If Mr. Melnick has his wish, they may be revived. In 2002, he formed the nonprofit Brooklyn City Streetcar Company, and he has spent the last three years meeting quietly with community leaders and city officials as a one-man advocate for trolley lines in Brooklyn.

The last trolley rumbled through Brooklyn in 1956, according the article. Maybe the idea would gain traction if it were sponsored by a Brooklyn knish brand á la Rice-A-Roni.

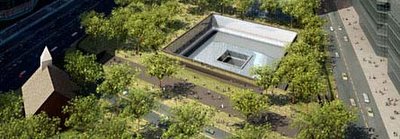

The weekend edition of "breathtaking inanity" is supplied by The Gutter, normally an architectural blog so dense with inside baseball BS, I don't even bother. But in an item that reacts to the NY Post's absurd article asserting that all systems are go at the World Trace Center memorial, The Gutter is for once worth quoting at length:

The weekend edition of "breathtaking inanity" is supplied by The Gutter, normally an architectural blog so dense with inside baseball BS, I don't even bother. But in an item that reacts to the NY Post's absurd article asserting that all systems are go at the World Trace Center memorial, The Gutter is for once worth quoting at length:Fact: When completed, in 2000-whenever, the WTC memorial will immediately become a plum target for nemeses and ne'er-do-wells, far and wide. Fact: The interiority of the memorial—all those grievers sandwiched underground between concrete walls—will increase this danger. Fact: Massive, disruptive, airport-style security will be required at all entry points, coloring the experience of 9/11 remembrance with a reminder of its cause. Fact: Until this basic reality is acknowledged, excuse our French, it's a death trap.

Okay, even if it weren't going to be a death trap -- which is the most important point, since it will be -- it is hardly all-systems-go. How this has all unfolded has got to be one of the biggest disappointments imaginable. The only thing worse is if it DOES get built the way it's currently "planned" and people do get hurt. We would be much better off if it laid fallow for another decade until everyone really had a chance to integrate what happened there and how to address it.

This past weekend in the Arts section, Herbert Muschamp of the Times demonstrated why he achieved such heights as an architecture critic, even if he wasn't always beloved by everyone in that position (he was moved over and replaced by Nicolai Ourousoff). Muschamp's manifesto in defense of Edward Durell Stone's "lollipop" building, The Secret History of 2 Columbus Circle, is one of the most brilliant pieces of cultural/architecture reportage I've read, with these graphs worth quoting at length:

This past weekend in the Arts section, Herbert Muschamp of the Times demonstrated why he achieved such heights as an architecture critic, even if he wasn't always beloved by everyone in that position (he was moved over and replaced by Nicolai Ourousoff). Muschamp's manifesto in defense of Edward Durell Stone's "lollipop" building, The Secret History of 2 Columbus Circle, is one of the most brilliant pieces of cultural/architecture reportage I've read, with these graphs worth quoting at length: I HATE TO BE THE ONE TO TELL YOU THIS, but the old, relentlessly mourned Pennsylvania Station was a dismal piece of architecture. A late arrival in the City Beautiful movement, the building tried to augment meager conviction with extreme colonnades. Walking into its cold, cavernous spaces was like arriving in Philadelphia two hours before you had to.

But so what if Penn Station wasn't Grand Central? It was a crime to tear down a building that had become so deeply impregnated with New York's emotional life. The yawning interiors had a distinctive atmosphere. Like a vast sponge for intense expectations, the station soaked up the psychic energy of arrival, departure, separation, reunion and waiting that had accumulated over the years along with the soot, water damage and flimsy commercial intrusions. The station met the new arrival with a dare: can you make the big city know that you're alive? There's nothing like debased Beaux-Arts design for throwing out a frigid welcome.

A building does not have to be an important work of architecture to become a first-rate landmark. Landmarks are not created by architects. They are fashioned by those who encounter them after they are built. The essential feature of a landmark is not its design, but the place it holds in a city's memory. Compared to the place it occupies in social history, a landmark's artistic qualities are incidental.

To find out why the building is "queer," read the whole article here. I took some pics at the Bryant Park Ice Pond this afternoon. Is there anything that New Yorker's won't do while using their cell phones? (Click photo to enlarge.)

I took some pics at the Bryant Park Ice Pond this afternoon. Is there anything that New Yorker's won't do while using their cell phones? (Click photo to enlarge.) Finally managed to get a post up on the New York Times real estate blog, The Walk-Through, about the fast-selling 1600 Broadway, the only luxury condo in Times Square.

Finally managed to get a post up on the New York Times real estate blog, The Walk-Through, about the fast-selling 1600 Broadway, the only luxury condo in Times Square.

"As 2006 begins, the great American housing boom is going to weaken, if not collapse. But that will not hurt the economy very much, and growth will continue at a good pace.

Or so goes the conventional wisdom."